Description

This symposium celebrates the centennial year of 1922 when T. S. Eliot’s book of poems, The Waste Land and James Joyce’s novel, Ulysses ushered in a new era of ‘High Modernism’ in European literary history. What the Eurocentric discussions of 1922 Modernism often forget is the fact that Rabindranath Tagore’s book of curious genre-bending texts, Lipika was published in the same year 1922 as was his play ‘Muktodhara’ (‘The Waterfall’). This convergence tells us that modernism didn’t happen only in European literature. In 100 years a lot of critical water has flown under the bridge and we have acknowledged modernisms in the plural as coeval global literary developments across the world. Laura Doyle and Laura Winkiel’s framework of ‘Geomodernisms’ and Sophie Sieta’s work on the little magazines, offering a global network of modernisms are cases in point. The recent publication of the global modernisms anthology, edited by Alys Moody and others have widened the scope beyond Europe, deep into South Asia and East Asia for instance. Bhavya Tiwari’s book on world literature in India beyond English, published earlier this year, has given urgency to the need to go deeper into the bhasha modernisms in India without being limited to the Indian English tradition. With the emergence of research fields like global transnational modernisms and world literature, we have come to examine the cultural politics of how literature travels across national borders to have seminal influence and how other literary traditions get reinvented in dialectical tension with such influences and encounters.

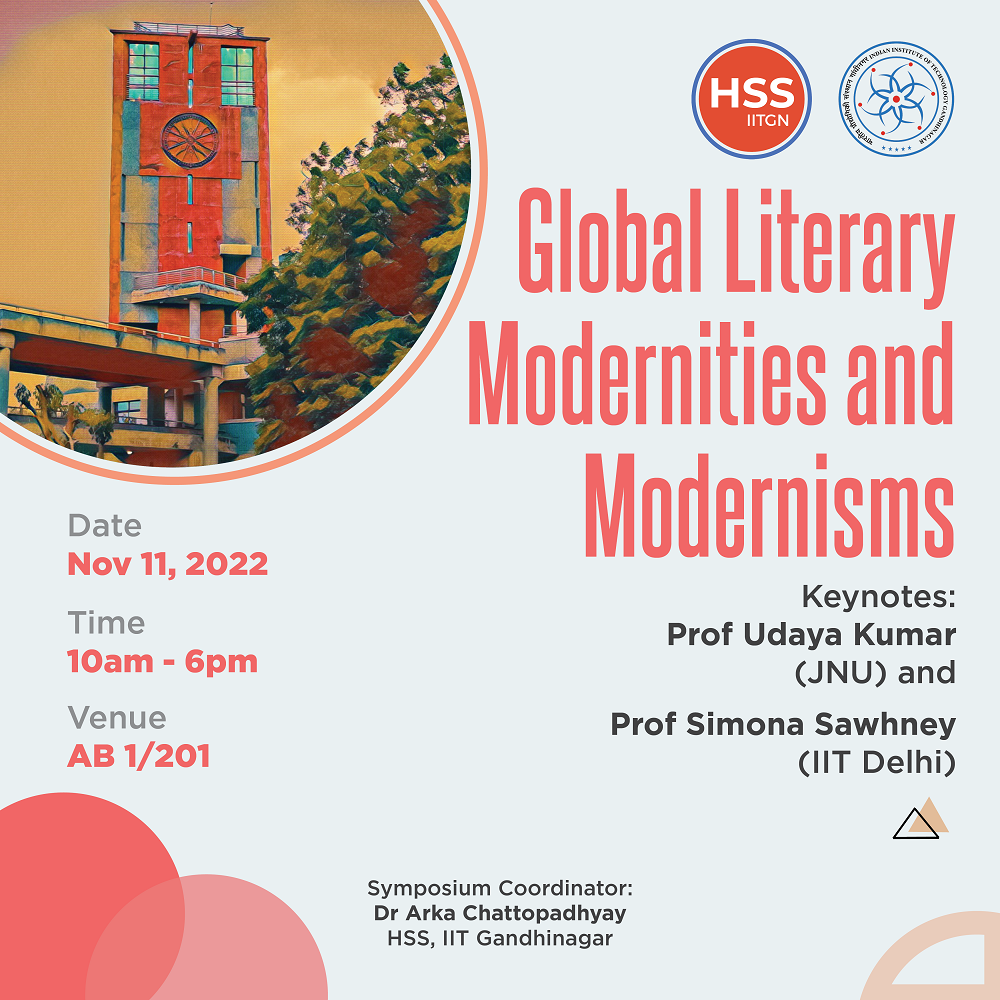

In this proposed one-day symposium with the two keynotes from JNU and IIT Delhi and the five IIT Gandhinagar doctoral papers, we want to think through the question of global literary modernities and modernisms as they stand in their complex spatio-temporal coordinate in the present. Prof. Kumar’s keynote talks about trans-local modernisms by locating literary modernisms in the diverse bhasha traditions in India that have an association with James Joyce’s project of memory in the Irish context. The paper allows us to see how modernisms can travel and produce narrative worlds, cutting across cultural difference, without letting go of the local scenarios of resistance. Prof. Sawhney’s paper continues this thread of contestation by engaging with modern Hindi-Urdu writers (Yashpal, Ismat Chughtai and Krishna Sobti). It explores aspects of political modernity that open up the paradox of modernity as change as well as disaster. This double valence with a critique of political modernities in India cements a critical modernism that may go against the political narratives of modernity. Udita and Arindam’s papers foreground ideas of migration and travel, crucial to any discourse on global modernities, as they study Miyah poetry of Assam and the Bengali modernist travel narratives (Sen and Gangopadhyay). Maithili explores the caste-question in the gastronomic modernity of Maharashtrian Brahmin women, revealed through the periodicals of the early 20th century. These papers attend to situate the habitations of

modernity in India. In Prashant and Parul’s papers, we turn to Europe and Mexico to see how modernisms unfold and ramify via questions of eroticism and language in poetry (Paz) and interrogations of inwardness through theatrical ideas of projection (Mallarmé). The symposium would be a way forward in situating global modernisms in 2022 in its complex ideational networks

with Indian and world literary traditions.